Not communism, but not nothing

The political economy of Labour's broadband giveaway

Out of nowhere, the Labour Party last night made a game changing move in an otherwise dreary election. It promised to roll out full-fibre broadband to the doors of every household in Britain, for free, by 2030.

It will do so by nationalising the broadband business of former state telecoms provider BT, and funding a £20bn digital infrastructure spend out of long-term borrowing. The press immediately dubbed it “broadband communism”.

Hordes of centrists dads took to Twitter to complain that they should be allowed to spend £20 a month on a crap copper wire internet service instead of getting an industrial strength version for free.

Here I want to explain the political economy of the move. It’s not just a retail giveaway to catch votes - it contains the seeds of a serious rethink by British social democracy about the relationship between wages, information and work. Here’s why:

Public good. Labour just basically reclassified the digital infrastructure as a public good, like the road system. Up to now, during the digital comms revolution, the entire physical infrastructure has been used as a rent-seeking opportunity by private monopolies, whose “competition” always seems to produce the same rip off pricing. Labour’s move is a statement that this can’t go on: better that the public owns the natural monopoly of fibre-optic cables, and entrepreneurs compete on a level playing field to sell you services over it.

Data democracy. Because the big broadband providers could never profitably wire up Britain’s rural and coastal communities, these areas were lagging further behind the already piss-poor British broadband system. This is a social guarantee to treat every household equally, rolling out the fibre backbone to places it does not exist, and then connecting every doorstep with ultra-high speed fibre.

Cost of living. Traditionally union-backed parties like Labour don’t do much to cut the cost of living. The implicit assumption is that you equalise society upwards through wage bargaining - on the assumption that social pressure to cut costs eventually feeds through to pressure for lower wages to the workforce. But this is what I hope will be the first of several eye-catching offers on the cost of living.

Cheapness. According to the British government’s own study, though a state monopoly roll out might take longer, it is the only format that delivers 100% coverage and costs £20bn compared to £33bn through the “enhanced competition” model the Tories preferred (kind of giving away the weird outcome of “competition” in a rigged neoliberal market).

And though it is not communism, this is no longer business as usual for Labour. This move fits perfectly the rationale I advanced in Postcapitalism: A guide to our future, and which I have privately argued with Labour decision makers: to attack the input costs of labour by attacking monopoly pricing and rent-seeking.

Here, instead of redistributing a slice of the profit share to the wages share, through wage bargaining, the principle is to reduce the input costs of everything - labour, machinery, services - and to strip away the pricing power of the monopolistic elite, while at the same time de-financialising consumption (depriving the finance system of its economic rents).

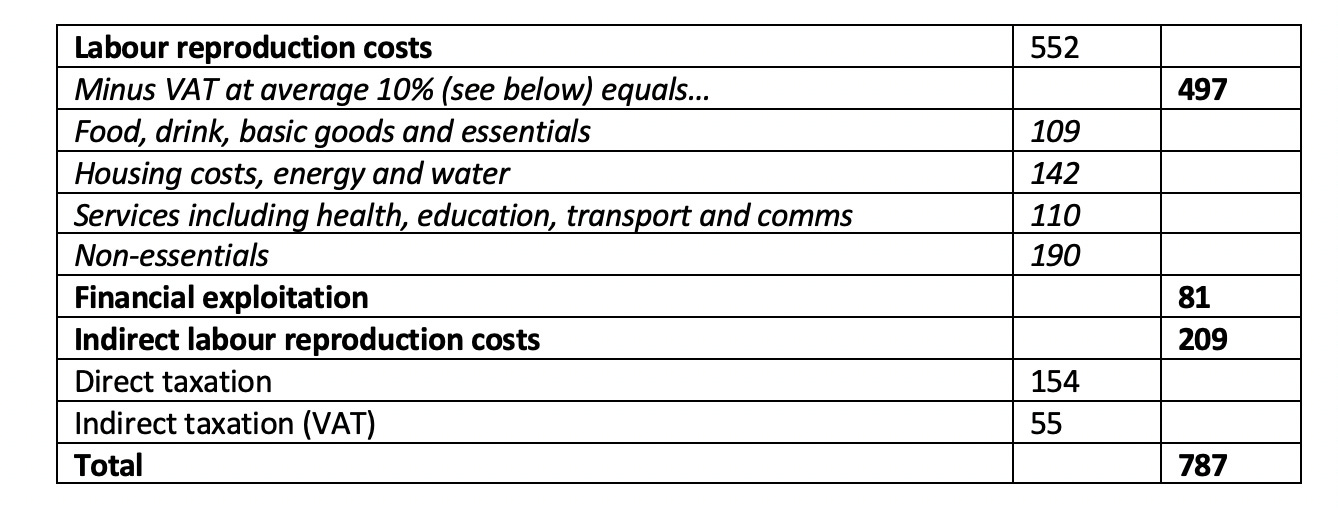

Last year I made a private study study of average UK household spending, reordering the categories to fit the Marxist labour theory of value. The ONS divides the average £787 spent each week into two broad categories:

Goods, services and housing (£554)

Direct tax, house purchases and pension contributions (£230)

According to the labour theory of value we need to know something different:

What is being paid by the worker to directly reproduce labour power (eg food, transport, comms)

What is being paid to indirectly reproduce labour power (eg taxes)

What money is being directly exploited via the finance system (eg credit card interest payments)

If you buy the idea that we are in a highly monopolised and rent-seeking era of capitalism, then item (1) is also likely to include goods that are priced systematically above the labour hours embodied in them.

And of course, none of this covers the wage relationship itself, in which the unequal relationship between worker and employer produces a surplus for the corporation.

In a highly-monopolised info-capitalism, this exploration of the consumption and financial aspects of exploitation suggests three lines of redistributive attack:

to identify, stigmatise and remove the monopoly pricing workers are subjected to in direct consumption;

to load the tax burden onto corporations and the super-rich, and refrain from increasing taxes like VAT which hit the workers hardest

to abolish financial exploitation

Here is the table I came up with by reordering the ONS categories: it shows how the average UK family is exploited by capital via finance system (£81 per week gross); and simplifies the categories in which we could look for exploitation via monopoly pricing:

Since this a thought experiment, it doesn’t matter whether the figures are exact - but you can see at least 10% of the average family’s outgoings are direct financial exploitation - and you can guess that a chunk of the “housing, energy, water, transport and comms” spending is spending that could be reduced by attacking monopoly power, reducing rents, energy bills transport and housing costs.

I see Labour’s move today as the first big example of a left party trying to do this. It’s not communism, but it is intellectually congruent with the post-capitalism thesis.

Overall, in the post capitalist transition, the aim is rapid automation, to de-link work from wages through universal basic services, the collapse the cost of production of everything, including labour power itself, to attack rent-seeking business models, and to attack the massive asymmetry of power and knowledge info-capitalism breeds.

This move ticks all those boxes.

It provides a universal basic service for free. It reduces the cost of reproducing labour power. It abolishes several rent-seeking business models. And it equalises access to fibre to all citizens, benefiting the poor and isolated rural and coastal communities.

The elite have derided the move, saying it will cost too much money, expropriate investors etc etc. But it is massively popular - whatever tonight’s oligarch-owned Evening Standard says….